How to read academic articles without overloading your brain

07 March 2021

For untrained eyes reading academic articles might be a daunting task. As I witness daily with students, it can alienate even the most curious people from learning something new.

Whereas PhD students have the advantage of tackling the academic reading skill down early on in their career (mostly because they have to), undergrads and even Masters students usually struggle with the academic lingo, big words, cumbersome sentences, and research domain-specific jargon.

As many academics can confess, strategies on how to read academic texts are the usual suspects on the agenda of many doctoral seminars across university programs of all levels. Some academics are better at relating to their audience through writing than others. With the rest of them, the reader has to struggle a bit.

So, before we reach the time when all the scientists, researchers and academics will write in a slightly approachable language, these are some helpful strategies on how to read an academic article from yours only.

Order matters

This might be an illustrative story too old for some to remember, but bear with me. Have you ever noticed the manner sports fans read their daily (printed) newspapers? They start at the back and only after they learn everything they need to know about their favorite team’s last night performance, they turn the pages back towards the beginning of the papers and start reading from there. What is not interesting to them is doomed to be skimmed, more intriguing pieces got more attention.

Believe it or not, this is how the reading of academic articles work (or can work) for you too. Only a couple of tweaks and steps are different.

First, you check the title of the article to see what is going on and what the main topic of the article is. Some authors disclose their findings right in the headline which makes your life way easier (yay!). Some use keywords to get the traction for their article, although the content doesn’t talk about the topic at all. Some are enigmatic and don’t tell you much, and it’s up to you to dig a bit deeper in the article itself to learn about its content.

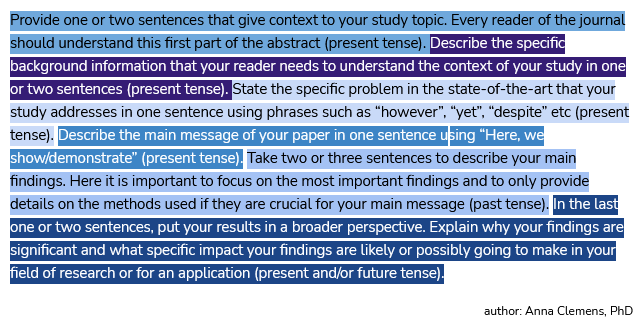

The second step is to read the abstract, which should be a summary of the article placed right before the article starts. You can think about it as a movie trailer. A well written abstract gives you a glimpse of all the important parts of the article without spoiling all the content. The quality and information disclosed in the abstract vary greatly across the fields, but Dr. Anna Clemens, who is a scientific writing coach I like following, gave a neat glimpse into the abstract anatomy which you can follow to make sense out of the one you read.

The next step goes contrary to the usual approach of reading. In the third step, you read the conclusion or discussion part at the end of the article to learn about the summary of the research described in the article. Why? Most academics summarize their findings and recapitulate in this part of the document what they described in a lengthy way in the article. At this point, you might aslo want to check if the article has an introduction where the same summary usually happens too. This varies based on the discipline and its norms on how to structure a paper, so don’t worry if one of the parts is missing. Reading this way also gives justification to my sports newspaper metaphor wink wink.

Essentially, this is where you are done with a so-called skimming, which is a method that millions of researchers use to quickly figure out if the paper they read is relevant to their research and should be included in their literature review, future projects, class, etc.

Skimming is not always the end goal of reading an article. Sometimes you need to know much more than what you get from just the superficial overlook. To get to a certain level of details of information you could then use in your own work (in a paper, presentation, etc.), as the next step you want to look at the headlines of different sections of the article. This will give you a brief notion of how the article is structured and what are the parts authors talk about. Also, if you need to learn only about methods authors used in their research, you don’t have to read other parts of the article. Headlines will tell you where to start and where to stop.

This is how my approach looks like in the practice on the first and last page of an article about Dark Patterns in the Design of Games respectively:

One tip before you go: A well-written paragraph starts and ends with sentences summarizing the main points of the paragraph. In a lot of cases, unless you are someone who has a reading FOMO, that’s enough for you to get the gist of the paragraph’s contents. Unfortunately, it’s not always the case.

TLDR; version:

- Check the title of the article to see what is going on and what the main topic of the article is.

- Read the abstract, which should be a summary of the article placed at right before the article starts.

- Read the conclusion or discussion part at the end of the article to learn about the summary of the research described in the article.

- Look at the headlines of different sections of the article to understand what each section is about.

- Read first and last sentence of the paragraph to get the gist of the paragraph’s contents.

Since the researcher should always give the credit where it’s due, I need to confess that I learned this strategy and tweak it to my own reading habits from the book Grad School Essentials: A Crash Course in Scholarly Skills by Zachary Shore. It’s been saving my time and brain on multiple occassions throughout my PhD.